The burial site of Kuttimani and the group killed in the 83 Welikada prison massacre revealed

Over the past few years, Sri Lanka has witnessed multiple discoveries of several new mass graves. Hundreds of human remains are being excavated from these mass burial sites, and subsequently, a call for an investigation supervised by international forensic experts, has emerged to reveal the burial site of Tamil prisoners killed in a prison. These Tamil prisoners have been brutally tortured and killed over a two day period by Sinhalese prisoners at Welikada Prison, four decades ago.

Tamil political activists and a group of relatives of the murdered prisoners demand a full investigation into the killings of those 53 people. This crime has been allegedly committed with the assistance of prison officials, whilst the state sponsored racist attacks in Colombo during Black July 1983 were escalating.

An international investigation

“Where did that government bury everyone who was killed, including my father? None of us exactly know what was done with their dead bodies. We only ask for a formal international investigation into the massacre and that the perpetrators be punished.” Yogachandran Mathivannan, the son of Selvarajah Yogachandran alias Kuttimani, who was killed in the 1983 Welikada massacre, said in an exclusive interview.

yogarajan

Yogachandran Mathivannan

Mathivannan also said that they learnt about the killing of his father, over the radio while he was in a refugee camp in India after fleeing the country. The government, however, did not inform the families in any way.

“After my father and the others were killed by Sinhala prisoners, the government deliberately hid that crime. How did they die? How were they cremated? Where were they buried? They didn’t say anything. We are still in shock, even today,” Mathivannan said in a broken voice. He was just 12 years old when his father was killed.

In the Borella Cemetery

According to past independent investigative reports and eyewitness accounts of the massacre, the murdered inmates had been loaded onto a prison truck and taken to the Borella public cemetery. There they were dumped into a pit piled with firewood, which had been dug in a secret location and subsequently burned.

M. K. Sivajilingam, a prominent political and civil activist campaigning for Tamil rights, stated that the current government has the ability to conduct an independent investigation and reveal the truth which has been kept hidden by several governments for four decades.

“Every government kept this hidden. Now this government says it is looking for buried crimes. We ask then, allow this massacre to be investigated as well. Because all of these people were killed while they were in prison under court orders. That means this was under government control. So, the government has a responsibility to investigate this. It is irrelevant which government it is,” former Member of Parliament Sivajilingam emphasized.

Both Mathivannan and Sivajilingam are unanimous in their demand that justice be served to the victims. They say a thorough invesivajilingam

M. K. Sivajilingam

stigation should be conducted without any further cover-up. They both emphasize it is imperative that an investigation be conducted with the participation of international experts, independent from the Sri Lankan government.

“I think the international community must intervene to properly investigate this crime. At least then we would be able to know what was done to the dead bodies.” stated Mathivannan.

This massacre was suppressed as an unimportant crime for 40 years under 11 Sinhala majority governments and 8 rulers, while mass graves have been discovered all over the country. Investigations had gone underway, even in a haphazard manner. The present Anura Kumara Government is the 12th regime and the 9th ruler since the massacre. Meanwhile the seventh mass grave was recently discovered in Sampur.

The first massacre

On 25th July 1983, 35 Tamil political prisoners held in the Chapel Ward on the ground floor of Welikada Prison were dragged out of their cells, beaten with sticks, clubs, iron rods and other weapons, and killed on the spot. Two days later, 18 more Tamil prisoners were killed in the same manner while prison officers and armed soldiers were watching. Independent investigative reports later revealed that most of the 53 Tamils killed had their limbs broken, eyeballs removed out and were dragged across the open space in front of the prison.

“My father’s eyes were gouged out while he was still alive. That’s how we got to know. His eyes had been gouged out like that because he had said that he wanted to see Eelam before he died,” Mathivannan said tearfully.kuttimani

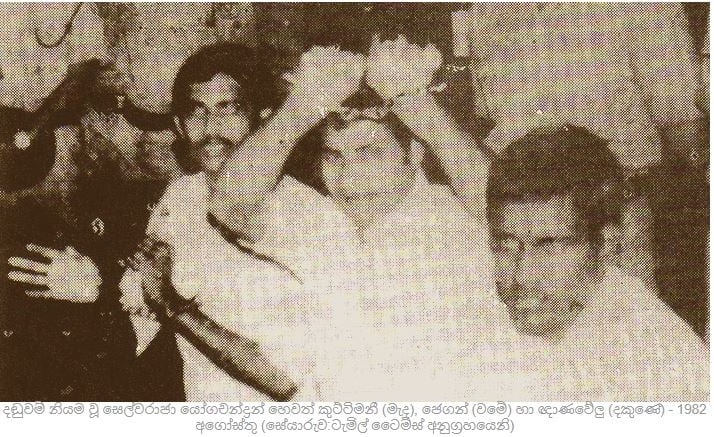

The Chapel Ward had four sections of cells, A, B, C and D, and the ground floor contained four more cells, A3, B3, C3, and D3. Six Tamil prisoners including Selvarajah Yogachandran (Kuttimani), Nadarajah Thangavelu (Thangathurai), and Ganeshanathan Jeganathan (Jegan) of Tamil Eelam Liberation Organization (TELO), who were arrested by the Navy in 1981 for the Nirveli Bank robbery and sentenced to death by the court, were held in cell B3 on the ground floor. All of them had appealed against their death sentences.

The reports mention that in cells D3 and C3 there were 29 Tamils and 28 Tamils respectively taken intocustody under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA).

In addition, 9 other prisoners were held in the Youthful Offenders Building (YOB). They included Dr. Dharmalingam, Kovai Maheshan, Dr. Somasundaram Rajasundaram, A. David, Nithyanandan, Father Singarayar, Father Sinnarasa, Father Jeyatilekarajah and Dr. Jeyakularajah. The Deputy Commissioner of Prisons at the time, Christopher Theodore Jansz, later confirmed that many of the people held in cell D3 were either suspects or were to be released soon.

However, cell A3 was different. It was said that the most dangerous prisoners who tried to escape were held there. All of them were Sinhalese. According to reports, many of the Sinhalese prisoners held in cell A3 were directly involved in the attack.

Sepala Ekanayake, who was serving a life sentence for the 1982 hijacking of an Alitalia flight was among those brands of criminals. Sepala Ekanayake was later stated that he had incited and led the Sinhala mob to carry out the massacre.

Independent investigative reports published later indicated that a significant number of prison guards were on duty during the day near the corridors on the upper and lower floors of the Chapel Ward, and that at least 15 guards were on duty at all times, especially in the narrow corridors near the iron-barred cells on the ground floor, where prisoners used to hang around. However, the number of guards were significantly reduced on the 25th – the day of the first attack.

The heat of the Sinhala racist mob that gathered near the Borella cemetery on 24th July, as well as the anti-Tamil racist attacks that were taking place in Colombo, was already felt inside Welikada Prison, say the Jaffna University Teachers for Human Rights (UTHR-Jaffna). Amongst such a terrifying and hostile atmosphere, a large number of prisoners from the lower section were taken out of the prison. It is unclear why. But it is clear that such action must have provided some energy to the violent Sinhala prisoners. Meanwhile, the Tamil prisoners who were sentenced to death were receiving daily newspapers. Accordingly, it did not take long for them to realize that anti-Tamil violence in Colombo was escalating. UTHR have stated in their report that between 10 and 11 am that day, a certain unrest was emerging from inside the prison, and at around 2 pm, a large group of Sinhalese prisoners had arrived at once from the direction of cell B3 and attempted to break down the doors and locks of the cells where Tamil prisoners were being held.

Inmate Manikkadasan, who was in cell C3, looked down from a nearby window and saw Tamil prisoners, who had already been killed or seriously injured after being beaten, being dragged by their limbs along the ground to the open area by Sinhala prisoners, while jailor guards watched.

A premeditated massacre

It is clear that the daily security arrangements inside the prison have been deliberately altered, and what is even more surprising is what the regular army unit was doing during the attack. The armed unit was stationed outside the main gate of the prison. According to UTHR, the statement given by the prison superintendent Leo de Silva during the magistrates’ investigation states that he shouted to the soldiers guarding the gate.

However, he himself has said that it was difficult for the soldiers to control the inmates who were high in numbers. It is also reported that more than 800 inmates were already being held in the Chapel section, which consists of two floors. He also added that the soldiers had left the area even though several bodies were lying on the floor of the corridor on the upper floor. But it does not appear that a larger unit of soldiers or the military unit guarding the main gate were deployed by the authorities or the top security chiefs to bring the situation under control.1983 rioters fire 1 0

Perhaps troops at the main entrance were also waiting for the Sinhala prisoners to calm down and allow them to carry out their attacks as they pleased. The attacks began with the violence that broke out near the Borella cemetery, where the last rites for the 13 soldiers who died in the war in the North were being held under state sponsorship.

The reason given by the authorities for deploying the military unit in front of the prison was the alleged suspicion that Tamil prisoners detained under the PTA would escape. However, authorities are yet to provide any explanation as to why the relevant military personnel were not called inside the prison to quell the violence, and if so on what grounds. Especially while the lives of those prisoners were being put in danger, as well as those who had appealed to higher courts and those who were about to be released.black july wdfudf

The security of the front side of the prison was entrusted to a platoon from the 4th Artillery Corps. Its commander was Lieutenant Mahinda Hathurusinghe. According to the statement given to the magistrate by the lieutenant, he along with 15 other soldiers were in the nearby military billet just before the attack. He also said that 5 soldiers were on guard duty near the main gate at that time. This was in addition to the 25 soldiers stationed in another guard house about 200 meters away from the military billet.

However, Lieutenant Hathurusingha says that a sentry at the main gate came running and informed him about the incident. Accordingly, he went to the prison premises with 7 other soldiers. The lieutenant had also emphasized that the attackers retreated as soon as they saw the soldiers.

Lieutenant Mahinda Hathurusingha

However, according to independent investigators, this claim is difficult to accept. According to the UTHR – Jaffna, the lieutenant’s statement doesn’t tally with the statement of the prison superintendent Leo de Silva. Following Leo de Silva’s statement, UTHR -Jaffna says that information is available to say the military did not intervene to control the attacking prisoners.

The soldiers were armed with SLR automatic rifles. UTHR also recalls that an investigation by Suriya Wickramasinghe, the secretary of the Civil Rights Movement (CRM) at the mahinda hathurusinghe time, had revealed that the soldiers had not fired a single bullet to protect the remaining detainees, despite the killings that had already taken place.

According to the statement given by the Deputy Commissioner of Prisons (Acting) Christopher Theodore Jansz at the inquiry, he immediately went to the Borella Police Station to seek help in controlling the situation and reported the incident to the Deputy Inspector General of Police R. Sundaralingam. Although a police team arrived later at the prison, the army had not allowed police officers to enter the prison, he added. The Deputy Commissioner also said that he did not receive any assistance from the army personnel or other personnel in the prison to gain control of the situation.

Surya Wickramasinghe, who has pointed out that this is a complete violation of the Prisons Ordinance, emphasizes that if a situation arises that is beyond the control of prison officers, it is their responsibility to call the police. She also points out that the army has no legal authority or right to act against it.

The army in violation of international humanitarian law.

Deputy Commissioner Jansz had made great efforts to save the lives of the prisoners who were already in critical condition after being beaten. According to his testimony, the army had continuously obstructed this, indicating that the prisoners had already died. On the other hand, Lieutenant Hathurusinghe had not provided any space for obtaining external assistance.

However, Jansz did not give up his efforts and had even called an army major on the phone and requested not to obstruct the transportation of the injured to a hospital. However, the major had also rejected Jansz’ request, saying that the approval of the Secretary of Defense was required if the injured prisoners were to be taken out of the prison. 480928681 2305983279773405 8568672144398504971 n

Deputy Commissioner Jansz

According to independent investigators, this is an extremely serious issue. It was Lieutenant Mahinda Hathurusingha who had blocked the transportation of the injured prisoners out of the prison for treatment. The investigators have submitted that the rank of Deputy Commissioner of Prisons, C.T. Jansz, is equivalent to that of a Major General or Senior Brigadier in military terms, and that an Army Lieutenant cannot interfere with the work of a senior officer with extensive experience. More importantly is the argument put forward by Suriya Wickramasinghe of the Civil Rights Movement. She alleges that the United Nations International Convention on the Rights of Prisoners has been seriously violated by the military chiefs including Lieutenant Mahinda Hathurusingha. The military cannot violate the right of prisoners to receive medical treatment and ignore the responsibility to provide such medical treatment. Surya Wickremesinghe also emphasizes that any member of the military who intervenes in such a task is not bound to obtain permission or orders from their superiors.

Therefore, military and police chiefs including Lieutenant Mahinda Hathurusingha have intentionally violated that convention and aided and abetted the killings.

This situation is made clearer by the facts revealed by Jansz in his testimony about what ultimately happened.

Jansz says that he had brought the need to hospitalize the injured to the attention of several senior military officers, but to no avail. Then he had called Army Commander Tissa Weerasuriya, who had arrived from Jaffna that same day, to inform him of the incident. He had, however, also shown little interest in it. He also made requests to his university batch mate, Deputy Inspector General of Police Ernest Perera, and Inspector General of Police Rudra Rajasingham, and immediately went to the National Hospital with the hope of hospitalizing the injured. He had met its Director, Dr. Lucian Jayasuriya, and made arrangements there.bradman weerakoon 758c4363 8057 4476 8e18 e2816cbb0e6 resize 750

Bradman Weerakoon

The testimony of Bradman Weerakoon, who was the Secretary to the President, also states that whilst all this was happening, President J.R. Jayewardene, Defense Secretary Colonel Candauda Arachchige Dharmapala and other high-ranking government representatives were at the Army Headquarters.

Post Mortem 1

The bodies of the 35 executed prisoners were handed over to the Colombo Chief Judicial Medical Officer’s Office within a few hours for post-mortem examinations. The Colombo Chief Judicial Medical Officer (JMO) at the time, Dr. M. S. Lakshman Salgado, had requested the police to produce the order issued by the Magistrate before conducting the post-mortem examinations, but the police had made a strong effort to avoid producing the same. In order to conduct a post-mortem examination, it is mandatory for the police to provide the order issued by the Magistrate to the JMO. If the Magistrate does not issue an order for a post-mortem examination or if the investigating police do not take steps to obtain such an order, the doctor has the right not to conduct the post-mortem examination.

The Colombo Chief Magistrate at that time was Keerthi Sri Lal Wijewardene. Dr. Salgadu had visited Judge Wijewardene’s house in Havelock Town, Colombo, to obtain an order for the post-mortem examination. In fact, that was not his job. However, given the massacre that had taken place and the need to do justice to the victims, Dr. Salgadu must have thought it was appropriate to personally meet the judge and request the order, no matter how irresponsible the police had acted.

Despite the fact that more than two dozen unarmed persons had been killed in the first attack, the Chief Magistrate had acted like someone who had come from another planet; as if he had no idea what had happened and what was happening. Otherwise, the police, who were responsible for informing him, may not have done so properly. In fact, the police had never requested an order for a post-mortem examination from the magistrate.

However, Dr. Salgado has repeatedly tried to explain the reason for his visit to the Magistrate, but this has been thwarted by the Magistrate’s interest in discussing other matters with the doctor. He also invited Dr. Salgado to have a sandwich and tea with him, as he had discussed the increasing drug menace in Colombo with great interest. Finally, when Dr. Salgado said that he needed an immediate order to conduct a post-mortem examination, the Magistrate had said, “Though I would accompany you to the JMO’s office, I would not commence inquest proceedings unless and until the Police made an application seeking such an Inquest.” This implies that the police had not made any request until then.

Judge Wijewardene later issued the post-mortem order in response to an official request made by Hyde de Silva, the Officer in Charge of Borella Police’s Crime Branch.

During the post-mortem examination, JMO Dr. Salgado’s assistant Dr. Balachandra, had taken photographs of the bodies since they are considered essential medical evidence within a criminal investigation. If a case is filed for murder, it is mandatory to call the doctors who conducted the post-mortem examinations as witnesses. In such cases, submitting photographs of the bodies as medical evidence is extremely common and important. However, the judicial medical office staff, who have expressed doubts about Dr. Balachandra, taking photographs of the bodies, immediately complained to the Deputy Solicitor General Thilak Marapone through prison officials, accusing the Tamil doctor of collecting evidence against the Sinhalese.

Balachandra, being a Tamil doctor, also would have had to pay a “heavy price” had the judicial medical officer Dr. Salgado not informed Marapone that he was the one who instructed Dr. Balachandra to take photographs of the bodies. Dr Balachandra may have shared the same fate as the executed prisoners.

Dr. Salgado appeared to be skeptical not only about the future of the autopsy but also about his own future. Some reports indicate that he sent the post-mortem report to forensic pathologist Professor Bernard Henry Knight, requesting to publish those in the event of his untimely death.

Magistrate Keerthi Wijewardene conducted the magistrate inquest at the Welikada Prison premises on the evening of the 26th. Secretary to the Ministry of Justice Mervin Wijesinghe had also been present. The evidence was led on behalf of the Attorney General’s Department by Deputy Solicitor General Thilak Marapone and his assistant Senior Government Counsel C.R. de Silva. However, the examination of evidence was extremely biased due to the fact that only the government side was represented at the inquiry. It is an extremely important legal principle to hear the views of the victims or their representatives in a preliminary inquiry conducted by the Magistrate. This is because it is considered to be primary evidence. However, this has not taken place with regard to the Welikada Tamil prisoner massacre. According to independent investigators, neither a single prisoner who got killed was given legal representation nor statements recorded from their families. The most surprising and illegal nature of the magistrate inquiry is that not a single Tamil prisoner who was injured in the attack or who witnessed the incident was called to give evidence.

Murdering witnesses

The survivors were not allowed to express their feelings or tell the truth about the horrors they had undergone. Kandiah Rajendran (Robert), who had survived the attack, had seen many things. His testimony, however, was not given any light during the Magistrate’s Inquiry. Kandiah was also killed during the second attack, perhaps with the intention of permanently concealing that testimony.

For whatever reason, Magistrate Wijewardene had ordered the police on the 27th to immediately produce suspects before him, if any.Thilak Marapana1

Tilak Marapana

But something else happened shortly after the Magistrate’s order. The Superintendent of Police Hyde Silva sought an order to dispose of the bodies of Tamil Prisoners under Section 15A of the Emergency Laws and Regulations Act. Deputy Solicitor General Thilak Marapone has not objected. Since the Magistrate had no legal right to object according to the Gazette, he granted that request, slamming the door on further judicial intervention. In fact, that was what the Jayawardene government wanted.

Hiding dead bodies under the guise of “public security”

The Jayewardene government had issued the gazette notification No. 254/03 dated 18 July 1983 that allowed for the disposal of dead bodies without a post-mortem. From that gazette notification, the state officials were given the authority to dispose of dead bodies without handing them over to the next of kin or any judicial or medical investigation. It was a gazette notification passed on the basis of executive immunity, overriding the Constitution, the fundamental law of the country, as well as the criminal law.Gazette page 0001Gazette page 0002Gazette page 0003

It was a gazette notification issued under the Public Security Act, which had already been made into law. It states that in terms of Emergency Regulations 15/A, any dead body can be kept in possession or disposed of, upon request made by a person not below the rank of Assistant Superintendent of Police or an authorized officer with the approval of the Secretary to the Ministry of Defense. It also states that the order is not subject to any other law or ordinance. Under that arbitrary law, the state authorities were able to bury the 1983 Welikada massacre, in order to mark it as a “non-crime”.

When the power to decide the criminality of an action or inaction is given to the political executive or the administration under it, outside the judicial structure, the independence, impartiality and the due process of justice itself are completely undermined. If an Act or a gazette introduced by the executive is powerful enough to conceal a murder without legal investigation, especially a massacre of unarmed prisoners held under state protection on court orders, what else can be said about due process in the country?

“Everyone who was killed was detained in prison. The government should be held responsible for those deaths. How can the court say that, then, this massacre was not a crime? Isn’t there anyone to be held accountable for those killings?” Mathivannan, the son of brutally murdered Kuttimani, asked.

The second massacre

Following the first massacre, the situation within and without the prison was extremely chaotic due to anti-Tamil racist violence that was unleashed throughout the country. The violence was escalating from assaults, expulsions, looting of property to the most brutal of killings. Even after the killings on the 25th, instead of taking steps to prevent a similar situation from recurring, the Jayewardene government had acted irresponsibly. In particular, a surviving prisoner later said that many officers in Welikada Prison had further incited the Sinhala prisoners.

The next 24 hours must have been a critical period for the other Tamil prisoners. They wouldn’t have forgotten the horrific way their fellow prisoners were killed just 24 hours earlier. The Tamil minority was already in the midst of hundreds of Sinhalese prisoners who had been instilled with murderous racism. It is therefore not unreasonable for them to be afraid of a returning death.

The first attack had already attracted worldwide attention. Not only for being a massacre of prisoners but also because an ethnic group was clearly targeted in addition to the suspicious nature of the Sri Lankan government’s response. There were strong demands to ensure the safety of the prisoners who survived the first attack. Deputy Commissioner of Prisons Jansz was also summoned to the Security Council meeting held at the Army Headquarters on the morning of the 27th.eljksd

Jansz had already warned the Secretary to the Ministry of Justice, Mervyn Wijesinghe, about the risk of a second attack against the Tamil prisoners who had survived the first. In fact, there was enough time to implement a diligent safety program to save the lives of the survivors before another attack. There were also sufficient reasons to suspect the threat. It is a lie to say that the state authorities did not have clear and unambiguous information about everything even by then over who were the attackers of the first attack. Who might have led it? Why did the army not take action to suppress the attackers? And why did the responsible parties not take action to save the lives of the injured? There is little doubt that the Army Commander, the Inspector General of Police, the Secretary to the Ministry of Justice in charge of Prisons, the Secretary to the Ministry of Defense, as well as high-ranking security officials and even the political powers right up to the country’s Executive President, already knew what had happened.

The Security Council had discussed that the lives of those who had survived the first attack could be in danger by further detaining them in Colombo based prisons. Although it was initially proposed to airlift the surviving prisoners to the Jaffna prison, it was later decided that they should be transferred to Batticaloa prison. However, before the remaining prisoners could be safely transferred to Batticaloa prison, the Sinhalese, with the full support of the prison authorities, took actions to destroy the lives of 18 more prisoners in the second attack.

Second postmortem

Even before the heat of the prisoners killed in the first attack had cooled down, Secretary to the Ministry of Justice, Mervyn Wijesinghe, had to make another request for the autopsy of the 18 prisoners killed in the second attack. In the second autopsy, the evidence for the Attorney General’s Department was led by Thilak Marapone and C. R. de Silva. This was also without the participation or representation for the victims.

Ignoring the warnings of a possible attack by Sinhalese prisoners, shows that the authorities have indirectly aided and abetted it. It is no exaggeration to say that the jailers of Welikada Prison have let a second attack go unchecked. This is clearly confirmed by examining the evidence given by prison officials at the second inquiry.

The Chief Jailor of Welikada Prison, W.M. Karunaratne, testified that he had received intelligence reports warning of a risk of violence targeting Tamil prisoners. The Chief Jailor further stated that after learning this, he had informed Jansz that very morning. However, in his testimony, the Tamils held under the Prevention of Terrorism Act had been referred to as terrorists. The clear indication is that those responsible for protecting them had categorized Tamils held under the PTA as more dangerous than the Sinhalese prisoners who attacked them. On the other hand, this characterisation also served to justify the killings.

To the cemetery by truck

Finally, the bodies wrapped in white clothes were loaded onto a truck and taken to the Colombo General Cemetery in Borella. Jansz had also seen the bodies loaded onto the truck. The Deputy Commissioner of Prisons testified that he saw the prison doctor, Perinpanayagam, examine the bodies and confirm that they were all dead.

The bodies wrapped in white clothes were then put into a pit dug in a narrow strip of land at the end of the Borella public cemetery and burned under police and military protection. The Jayewardene government must have thought that by burning and destroying the bodies, no biological evidence would remain.

Evidence of a crime is not just limited to biological evidence. Thus, it is impossible to bury any crime in this world forever. No matter how much one tries to hide the evidence, there is a vast amount of evidence preserved not only around us but also in the hearts of people. Such evidence could be said to exist in the case of the 1983 Welikada massacre also. The whole world knows who had been killed, even though the bodies of those killed were cremated clandestinely without being shown to their loved ones. Their loved ones know to name their husbands, fathers, brothers, and close friends who had been murdered.

No government or law can erase such a memory. Secondly, the information and the written reports of a post-mortem examination or any magisterial investigation conducted at any level are hard evidence. However, the rulers who cremated the dead bodies did not have to take much effort to burn the investigation reports. However, when one looks beyond that, the modern world has the necessary technology and data analysis methods to investigate such crimes even after many years. It is proudly stated that there are Sherlock Holmes-like investigators in the Anura Kumara Dissanayake government. This is a great opportunity to display their ability showcasing their sharpness and intelligence in criminal investigation.

Now, all over the country, mass graves are being dug up. The people buried in them are people whose identities have not been scientifically confirmed, so far. But the situation with the Welikada massacre is different. The place where they were burned and buried is no longer a secret. Because some time ago, an eyewitness to the incident had told the media what he had seen. He was a worker at the Borella Public Cemetery. According to him, on that fateful July night, a soldier in a heavy earth-moving vehicle had dug ten-foot-long, wide and deep pits at the edge of the Borella cemetery without any permission.

When the Borella Cemetery caretaker informed this activity, the Mayor at the time Ratnasiri Rajapaksa ordered that the military be allowed to continue with their work.

“Then two army trucks arrived. When I got in, there were 35 bloody bodies of males. The army rolled them over into the pit,” Anees Tuan, a Colombo Municipal Council worker, told journalists in Colombo nearly three decades later. The next day, 18 more bodies were buried. Tuan believes that these were the Tamils who died in the Welikada massacre, including Kuttimani.

It is not known whether his evidence, or that of the Borella cemetery caretaker or Mayor Ratnasiri Rajapaksa, was examined at the Magistrates’ Court.

It is no secret who were killed, where they were buried or cremated.

“We ask for only one thing. Please conduct an investigation into this at least now. As far as we are aware, they were buried in the Borella cemetery. It is also said that they were burnt. However, there must be old records, right? The government and the Colombo Municipal Council, which owns the Borella cemetery, are now one. So, they can conduct an investigation into this now and reveal the truth,” Former Member of Parliament M.K. Sivajilingam emphasizes.

So, what needs to be done now is to conduct a transparent investigation into the matter. The singular and steadfast demand of the victims is an investigation with the participation of international experts. It is a demand that cannot be dismissed in any way. Because they are filled with doubt and disbelief that justice can be served through the Sinhala state itself for a crime that has not been investigated through a local mechanism for forty years and was suppressed within the first few hours of the crime through state intervention. They are ready to testify and submit their information in an international investigation, no matter where they live in the world. They are ready to fight for justice, even if they have to sacrifice eyes, ears, flesh, blood or anything, knowing that their loved ones have been killed and burnt to ashes.

Seeking justice at the cost of eyes, ears, flesh, and bloodJ R Jayawardeena 2019.08.31

“Justice must be served for my Appa and everyone who was killed. We are ready to do whatever we can. We are ready to scarifies our blood, flesh, and even bone marrow to find evidence for this crime,” Mathivannan said in a shaky voice, adding, “We do not expect justice from the Sinhala government. We know that it will never happen.”

Although the Jayewardene government suppressed the Welikada massacre without allowing any judicial intervention, it is also known that a group led by Suriya Wickremesinghe of the Civil Rights Movement had painstakingly collected testimonies, including eyewitnesses, and filed 35 cases in court. If the history is dug up, it wouldn’t be hard to deliver justice for such a massive crime even after 40 years.

The 1983 Welikada massacre was neither an accident nor a mistake. It was an organized killing spree. The live participants in that massacre were not only Sinhalese prisoners. From some illiterate lumpen prisoners to the executive president of the country, classy English Junius Richard Jayewardene who was also a lawyer were eager participants. The Deputy Solicitor General of the Attorney General’s Department, President’s Counsel Tilak Marapone, who conducted the evidence, was a top tier member of the United National Party. He was appointed as Attorney General very shortly after the massacre (1992/95). Later, he entered active politics and served in several powerful ministerial positions. The appointment of the Minister of Defense in 2001 and the Minister of Law, Order and Prison Reforms in the infamous Good Governance Government of 2015 was thanks to the power and glory of all the dark memories of the past. The fact that someone who worked to cover up a genocide while playing a key role as the government’s chief legal advisor – the Attorney General, and then being appointed as the Minister in charge of the same subject almost two decades later is a clear indication of the reality of Sri Lanka’s criminal justice system and the state’s relationship with it.siva

Siva Pasupathy

The 1983 Welikada massacre once again demonstrates how powerful state criminalization is and the administrative machinery associated with it. This is over and above the country’s justice system. At the time of the massacre, many powerful positions in the country were held by Tamils. However, the political impunity associated with state crimes had rendered all of them into invalid official rubber stamps.

When the Welikada massacre took place, the police chief of the country was Rudra Rajasingham. One of the Colombo area Police chiefs was also a Tamil. That was DIG R Sundaralingam. Deputy Solicitor General Tilak Marapone’s head of department, or rather the Attorney General, was Siva Pasupathi. What does this show? Just because there are Tamils in high positions, they are rendered hopeless when it comes to justice within the Sinhala state machinery.

Memories of massacre that didn’t stop at Welikada

It is not just the Welikada massacre; the subsequent killings and massacres targeting Tamils in prisons and detention centers have not yet been brought to justice. The 1997 attack on Tamil prisoners in Kalutara Prison, the 2000 October 24 attack on detainees at the Bindunuwewa Youth Rehabilitation Center by villagers, and the 2012 beating to death of political prisoners Ganesan Nimalaruban and Mariyadas Del Rukshan by jailers in Vavuniya Prison are all extra judicial killings for which justice has never been served. In the attack on the Bindunuwewa camp, 26 youths under the age of 21 were brutally tortured, beaten and killed, but all the camp officers accused of failing to prevent the attack were later acquitted by the court.Nimala Reuben 2022.10.29

Chief Justice Mohan Peiris, who dismissed the fundamental rights petition filed by the mother of Nimalaruban who was killed by jail guards in Vavuniya prison, had said that relatives of terrorists like Nimalaruban are trying to obtain political asylum in foreign countries by filing fundamental rights petitions. Mohan Peiris, a hardline Rajapaksa supporter who claimed that he ‘knows very well’ that Nimalaruban was a terrorist, also said that the deaths in the ‘clashes inside the prison’ cannot be interpreted as a violation of human rights.

He was appointed as Sri Lanka’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations in New York by Gotabaya Rajapaksa and carried on in that position for eight months under the National People’s Power government led by Anura Kumara Dissanayake.

Kuttimani’s son Mathivannan, with an emotional and broken voice, finally said:

“We cannot expect justice from Sinhala rulers. But at least tell us where everyone, including my Appa, was killed and buried or burned. Then we can make an offering of a flower or light a lamp to bring some relief to their souls.”

(K. Wijesinghe)